What it's like to go through an IPO at a startup

Here’s the story of my startup experience

When I started my first job out of college, I had no reason to be overly optimistic about my financial future. My offer from Tableau Software as a “Marketing Data Analyst” was a little underwhelming: $29,000 per year with a 10% bonus based on company performance.

And 1000 stock options.

Truth be told, I wasn’t very excited about the job. As an economics major, I had been working hard to make it into the financial industry and had even interned at a wealth management company in the Summer of 2008 with the hope of eventually doing something similar when I graduated. I had always been interested in economics, money and investing, so I was excited by a career that could let me focus on all three and potentially gain insight into the tools that wealthy people used to get ahead. If you want to learn how to make yourself a hamburger, get a job at McDonalds and make someone else one first.

In my role as the intern I was largely responsible for putting together the quarterly statements we sent to our clients. These people had a lot of hamburgers. Like millions and billions of them. Although I could only gain a small amount of underlying strategy and technique by looking at the quarterly reports, I did learn a lot about the different tools that wealthy people had at their disposal. Interest rate swaps, margin facilities, hedge funds, private equity, fund of funds, and options. One client was a board member of a large insurance company, and as part of his compensation he had over 3,000,000 shares of stock options. I didn’t really understand what they were at the time, but I did understand the tally at the bottom of that statement: $15 million. It was a figure I would remember, and a tool that I would log in my memory.

Unfortunately, as I started looking for a job in the summer of 2009, the entire financial industry was falling apart around me. I interviewed for 9 months and had little to nothing to show for it. I had been eking by on $10 an hour at a temp job as a reporting analyst at another wealth management company in the hopes that it might turn into a full time job. Obviously, that didn’t happen.

After months of fruitless applications -many of them for jobs selling insurance on 100% commission- I finally landed two promising interviews. The first one was at a two person wealth management company as an assistant. It paid $35,000, and my life would be spent sending faxes and printing quarterly reports. It was in the industry I wanted to be in, though.

The other role was at Tableau Software, a small analytics software startup, where I would be using the analytics skills I practiced at my wealth management internship as a data analyst in the marketing team.

Surprisingly, I got offers from both. Even though Tableau paid less and wasn’t in the finance industry, it seemed like a company on the move. My day to day life would be significantly more interesting. The lower pay stung, but I took the Tableau offer. I figured I would have more opportunity to stand out analyzing data at a fast moving company than sending faxes at a tiny wealth management company.

Plus, I was intrigued by the stock options. I remembered the client from the first wealth management company who had added $15,000,000 to his already sizable fortune with stock options. It wasn’t just outright greed that piqued my interest (although as an insanely poor college student I have to admit that greed did play a part). I grew up in a family of real estate entrepreneurs, and I was excited about the potential to own part of Tableau. Even if it was an infinitesimally small portion of the total company, I would be an owner (no comma) and I would benefit from the success of the company in the same way that the founders and early stage investors would.

I knew next to nothing about how my stock options worked, how much they would be worth, or how they were taxed. I didn’t even know that those were questions I should be asking. I did remember a couple of classes in college that briefly discussed financial derivatives, so I broke out my old textbooks and re-read the section on options at a high level.

What I learned wasn’t surprising: they give you the choice (hence “option”) to purchase an underlying asset (the stock) at a fixed specified strike price up until some point in the future (the expiration date). Naturally, if the price of the stock rises over time to a level above the strike price, the options have value: you can use the option to buy low, and then sell at the current price.

My own grant from Tableau was fairly easy to decipher. I received 1000 shares at a strike price of $1.00. These shares would vest (become usable) over the course of 4 years, with 25% of the shares vesting after 1 year and 1/48th of the shares each month after that. My options expired in 2019, meaning that I had to exercise (use them to buy the stock) before that date.

I had no idea at the time, but this is basically the most bog-standard ISO grant you could possibly receive.

Although the vesting part was still a little confusing, my brain started chewing on the concept immediately. If the stock price went to $10, then I could purchase my 1000 shares for $1 each. That meant I would make $9000 if I sold my shares:

$10 x 1000 shares (sale price) - $1 x 1000 shares (cost to purchase) = $9000

Although that was exciting, it was also a little depressing. My dream was to make enough money to start investing in real estate like my family. To get started doing that, I’d need a lot more than $10,000, and that just wasn’t going to happen. To make $100,000 off of my 1000 share grant, I would need the share price to go up by over 100x. To make a million it would need to go up by a staggering 1000x.

Expecting the company to grow 100x in value was a crazy expectation, and I knew enough at the time to temper my expectations.

I put my stock option folder away in the closet for safekeeping, and focused on working as hard as humanly possible. I wasn’t going to make a fortune from my stock, so I might as well try to get a promotion and a raise. Since I made so little I was working from paycheck to paycheck, and you could say that I was highly motivated to change that.

Almost a year and a half later, all of my hard work paid off. My boss called me into her office and sat me down: I was getting promoted to “specialist”, whatever that was, and I had received a 24% pay bump to $36,000 a year. Of course, I would also be receiving an additional 2000 options.

“Wait… what?” I said to her, a little surprised. I had been working under the assumption that I would never get another option grant. She sat me down and explained to me that each year every employee received a new grant which would start vesting under a new 4 year schedule. My new grant started vesting in 2011 and expired in 2021. In this way, I would never “run out” of options and would always be incentivized to remain at the company and work hard. There were even grants for promotions, and special grants for outstanding service to the company.

This totally and completely changed my attitude towards my options.

If I continued to get more shares each year, and managed to snag a few promotions and special grants along the way, I could potentially rack up thousands and thousands of options. Plus, after two years at Tableau the company’s prospects were looking significantly brighter. The economy was pulling out of the recession and companies everywhere were investing heavily in data, analytics and efficiency.

Assuming all of these things continued as planned, I might be able to walk away with a significant amount of money. Not tens of millions, but maybe a million or two. Enough for me to start investing in real estate and start “managing my own affairs.” For a kid making $36,000 a year, that was pretty exciting.

I got back to work. I wanted every option I could get my hands on. I also started doing some more research into how stock options actually worked, particularly in regard to taxes. My assumption had been that they would be taxed the same as income, but it turned out that this wasn’t the case. If I could scrounge together enough money to purchase (aka exercise) my shares before I sold them, I might be able to significantly reduce the taxes I paid on the options. Instead of paying income taxes for the whole amount, I would pay something called the Alternative Minimum Tax on part, and income tax on the rest. It was confusing -which is why I devote a whole section to taxes in this book- but the potential savings was certainly worth the mental exercise.

Although it would come back to haunt me later, I never did exercise any of my options early. With only $36,000 a year in income, it was hard to scrounge together $1000 worth of extra change to purchase even my initial grant. I knew I should, but I couldn’t, and I was way too busy to worry about it.

Everyone at the company was focused on a much more important goal: the IPO (or Initial Public Offering). Up until the IPO, as a private company there was no way any of us could sell any of the shares we were accumulating. The moment we went public our options would turn from theoretical slips of paper to something of real value, because we would be able to sell the shares on the stock market.

I continued to work hard and managed to get promoted a few more times. By 2013, I had received grants totaling over 11,000 shares.

-2009: 1000

-2011: 2400

-2012: 4000

-2013: 3600

None of them were at a strike price of more than $7. Although no one knew what the shares would be worth on the open market, the initial IPO filing said that we were shooting for a price somewhere in the range of $20-$30. Feverishly working the math in my head, at $30 a share, my stake in the company would be worth around $330,000. Not too bad for a 26 year old kid making $50k a year! Even with crazy Seattle real estate prices, that was enough to get started real estate investing.

As it turns out, my shares would be worth significantly more than that.

The day we went public in May of 2013, the entire company was camped out in our offices, awaiting the first trade with baited breath. Our executive team had flown to New York to ring the bell at the NYSE where the company would be listed. They had even flown every single employee that started before September of 2009 out to the NYSE to witness the event in person. As it turned out, I was the very first employee to be hired after that date. I had just missed the cutoff. Although I should have been disappointed, I didn’t care at all. The markets were about to determine the fate of my options, and the sentiment was bullish.

All of us employees waited in Seattle, glued to CNBC, eager to see how much our shares were actually worth.

If you’ve never been through an IPO before, it’s an amazing experience but it’s difficult to explain. It’s a little bit like Christmas morning as a kid. You know that there’s something special sitting under the tree, but you don’t know what. You’re excited, but you’re also a tiny bit nervous, wondering if you got what you wanted.

The market opened, and we started watching the bid price of $DATA (our new stock ticker) go up, and up. On the day of an IPO, the rest of the market starts trading before the new issues. The market puts in their orders while insiders and investment banks who hold the shares wait as the price goes up to try to maximize the value of the shares they sell. No one wants to be the first person to give up their shares.

Tableau was off to the races. First the bid hit $31. Then it creeped up to $37. $41. At first people were happy. Then they were excited. Then they were exuberant. It felt like a scene from The Great Gatsby, or some other roaring 20’s movie where everyone stares at a ticker tape spewing higher and higher numbers.

I remember looking at my colleague and telling him I hoped it would start trading soon. I didn’t want it to go so high on the open that we would spend years “earning back” the valuation, and potentially exposing ourselves to big selloffs if we didn’t meet the extraordinarily lofty expectations of the market. Although it didn’t play out like that, my intuition would end up being correct later on.

Tableau finally opened at $47 and closed the day at $50. That day, every employee of Tableau Software got exactly what they wanted, and a whole lot more.

I was stunned. We opened the champagne and started celebrating. It was complete and utter euphoria. Dozens of people in the room and on the NYSE floor had been made into millionaires almost instantaneously. Even me, a 26 year old kid that still hadn’t quite figured himself out, was sitting on over $550k in stock options. My hard work (and incredible superhuman luck) had turned out in my favor.

You can’t imagine how happy I was I didn’t take the wealth management job. Now, instead of tinkering with someone else’s portfolio, I had to start worrying about managing my own (extremely nascent) wealth.

It was also a little nerve-wracking. Although our shares had value, we couldn’t sell them until November of that year, 6 months after the IPO. This “lock up period” is a standard component of stock option compensation. If the company let everyone sell their shares right after the IPO, the stock price would tank, so insiders were restricted from sales until later. I just hoped the shares would stay above $50. I had already baked that price into my mind, along with my fancy new net worth, and it would be seriously disappointing if it went down before I could sell. As luck would have it, the price was going up, and by the time the lockup period ended my shares were worth $65 a piece. But, I’d need to exercise my options before I could sell them and turn them into cold hard American dollars.

You might think that this is “the easy part,” when you’ve vested your shares, the IPO has happened and the lock up period is over. Let me tell you, it’s not. Although it’s nice to be able to sell the shares, there are numerous considerations I had to grapple with at the time.

First of all, I needed to get the money to buy my shares. I hadn’t exercised my shares earlier, so I needed to purchase every share I wanted to sell. I was still completely broke even though I had gotten a few raises since I started, so I had to do something called a “cashless exercise” where a portion of the shares I had were used to pay for the exercise. Because I needed the money, I also immediately sold the shares I exercised.

Then Uncle Sam came into play. I ended up owing income tax on the entire amount that I had sold. Although I only made $50k a year at the time, the sale was large enough that it catapulted me into the higher tax brackets. I’ll go into detail later, but for now suffice it to say that the tax bill was significantly more than a years earnings for me.

To try to reduce my tax bill for future stock purchases, I also used a large amount of the proceeds from the stock I sold to exercise some of the rest of my shares. This way, if the stock appreciated further from $65 -and I didn’t sell for a year and a day- I would only have to pay capital gains tax on the appreciation above $65. Don’t worry, I will explain all of this in excruciating detail later.

After exercise costs, taxes, the new tranche of shares I exercised, and setting aside some money to pay taxes on the new set of shares I had exercised, I had used up almost 85% of the dollar value of the shares that I had exercised.

This is what can be so confusing and dangerous about stock options: just because you see a huge number in your brokerage account doesn’t necessarily mean you can turn those numbers into an equal amount of dollars. You are always in a hamster wheel of paying to exercise, paying taxes, exercising more, and setting money aside for taxes the following year for the shares you exercised the year before.

While I was figuring all of this out on the fly, the stock price was gyrating wildly, with a similar effect on my emotions. In early 2014, our stock had rocketed up to $100 per share. The shares I had remaining (along with the new grant I had just received) totaled more than $1,000,000 on paper. But, I couldn’t sell.

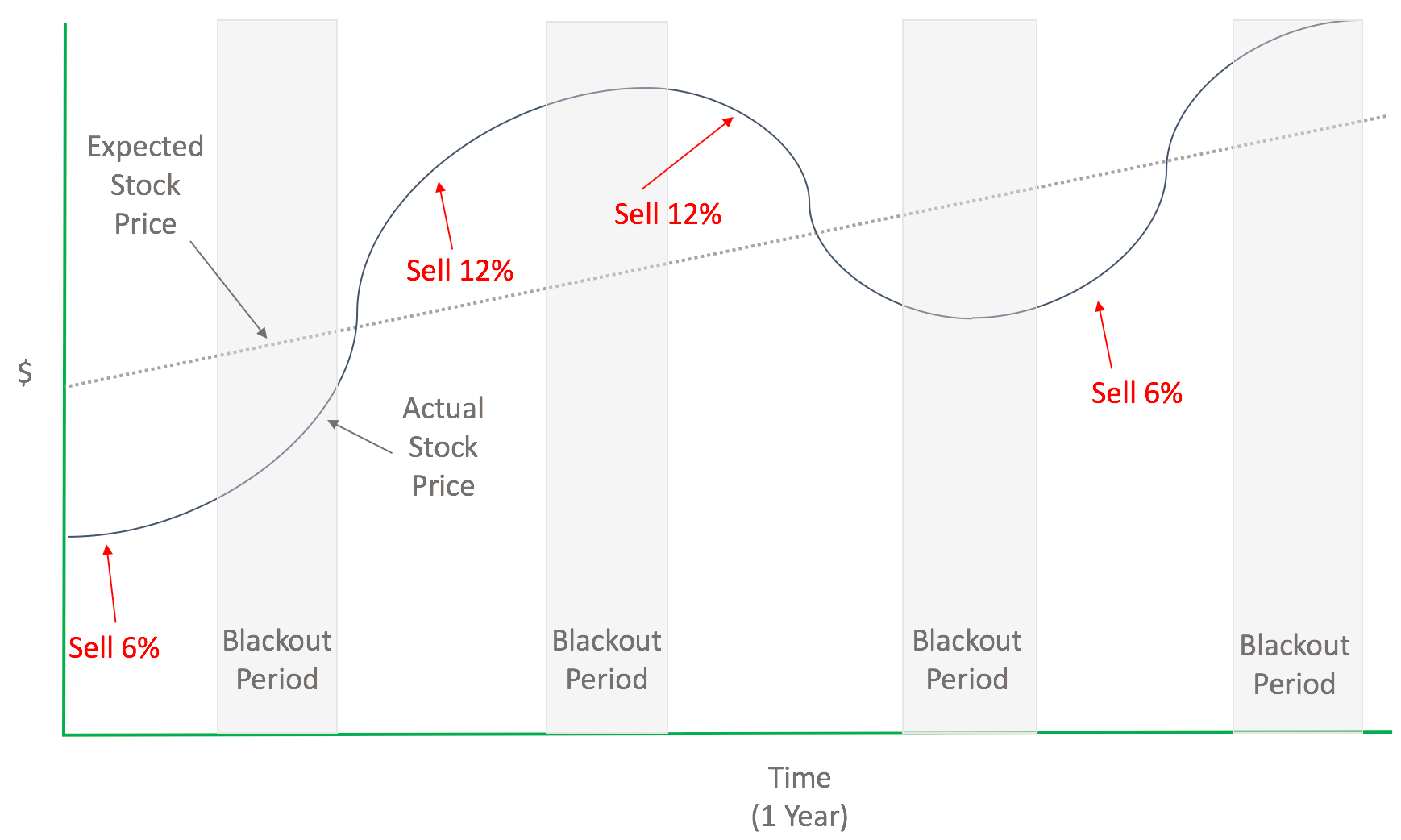

Remember the lock up period? Well guess what. There are 4 lock up periods a year once a company goes public. In an effort to avoid the potential of insider trading, most companies restrict their employees from selling shares except for within a brief period after each quarterly report. As I salivated over the prospect of $100 a share I watched as the price started falling, and falling, and falling some more, back down to a low of $54 in May. Now I was worth $500k on paper, half of what I was worth a few short weeks before. It was absolutely heart wrenching to watch. Luckily, that was just one leg of the roller coaster.

In July of 2015, Tableau hit an all time high of $130. My net worth, which was almost entirely Tableau stock, was well above $1m. I was 29.

Unfortunately, this was also during a lock up period, so I couldn’t sell. Truth be told, I wasn’t even sure if I wanted to sell. What if it went up to $200? Or $300? I was smart enough to know I should sell some to lower my exposure, but it was a hard decision to make. The fear of missing out is an enormous elephant that will always be on your back while you hold stock options in a publicly traded company.

By the time I was finally able to unload some shares, the stock price had crashed back down to $100. For a while it stayed around there, until the beginning of 2016, when it cratered to $40 - significantly less than the IPO price. I was able to offload a large portion of my shares at higher prices, but I certainly didn’t get the best price I could have for all of my shares.

By February of 2017, I had been through a wild ride. Even though I had been worth more than $1m on paper, I had only turned the 11,000 shares I had been granted into around $600,000. With exercise costs, taxes, and the wildly gyrating stock price, it was a huge challenge to turn my paper million into a real million.

Although it wasn’t the best outcome, it was still several orders of magnitude better than I had expected to do when I had seen my initial 1000 share grant. It’s a windfall that 95% of Americans would salivate over. I was able to buy an investment condo like I had dreamed of, pay off my debts, and set aside $100k for investments in the stock market.

With a relatively small amount of options left to vest, and Tableau becoming more corporate by the minute, it felt like the right time for a new company, a new role, and a new startup adventure. Having had a taste of the startup experience, I wanted to try it again. This time, I knew what a future success looked like. I knew how to use my options to the greatest advantage. I was also more senior and could secure a significant initial stock option grant. This time, I was resolved to turn my knowledge of the startup game into a much more significant fortune.

Around the same time, I also had an important realization. Although many people will never have the desire, the money, or the skill to become entrepreneurs in their own right, almost everyone can find a company to work for that grants stock options to their employees. There’s nothing special, or even really that interesting about what I was able to do with my options at Tableau. It happens every day. And unlike entrepreneurship or investing, it doesn’t require special skills or money to invest. Anyone can do what I did.

“But, I am not a software engineer,” you will probably say. Neither am I! Startups need salespeople and marketers, operations and project managers, HR, finance, accounting, legal, product management, support and hundreds of other jobs I haven’t even heard of.

“But, I don’t live in San Francisco.” No problem. There are startup scenes all over the country, and startups hire people all over the world to perform different tasks in their local market.

“But, I want to work for a bigger, established company… I don’t like tech companies.” No problem. There are plenty of companies outside of the startup scene and world of technology, like pharmaceuticals or biotech, that offer options as an incentive. They may not offer as much upside potential, but there are certainly opportunities to be found.

Although there will be some that have trouble finding the right company with the right job for them in their market, the vast majority of people can find a way to work for a company where equity is offered as an incentive.

The real question you should be asking yourself is “how could I let myself work for a company I am not a part owner in.” By definition, your time is incredibly valuable. You need to put it to use generating as much money and a much future potential as possible. Every minute here is a gift, and it’s silly to waste it.